|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

An oblique path of intervention It is not just about a place (or many places): a city, a village, a sub-city; its scapes, its structure / setup, places, buildings, people, – of prominence and those ignored, of their individual and collective histories. As one pans across the works of Rafeeq Ellias it is evident that to Ellias it’s all been a matter of constant exploration – be it of different lands or people across the globe, or that of understanding history or the current times - from a larger macro view to a highly intimate, individual / personal perspective. And in doing this Ellias constantly shuttles between many worlds, playing many roles. Once he was thoroughly into the glamorous fashion, advertising world, which he terms as “the business of ideas”, and over the time started exploring various spheres. Ellias believes that it was his travel that introduced him to another world, a raw world, which gave him a greater understanding of humans – their concerns and relations to a larger system which they were an entity / element of, and a sense of understanding politics through an analytical and critical approach. He becomes a part of these worlds / individuals, which / whom he captures, and blends well with them, and at the same time abstains from diluting his personal identity. With this he places himself at a vantage point, and undertakes an oblique path of intervention; as he captures terrains, events, and many other physically / visually present elements, especially individuals. To Ellias portraits remain his particular point of interest. The issues that tail are those of how, is / are the individual(s) being portrayed; as the works introduces the person(s) still in time to the viewer(s). From

the chic models with a ceramic glaze complexion, the graceful

ballerinas with their nearly el Further, there is evidently a constant oscillation between the outer viewer’s world and the inner, intimate, personal world of the individual being photographed. To the prior it is the character revelation and comprehension, and for the latter the retention of the personal / self. From the viewers end, even while saying that the viewer is not well equipped to employ a judgemental, subjective yardstick, it is also true that these photographs / portraits act like a window into the “other”, the non-physical aspect of the individual who is being captured, leaving it open for interpretation. And part of this ambiguity relates / crops from what / who is being depicted and (how) the manner of depiction - of what needs to be shown and what to be eclipsed. Such that there is a strange interplay between the – expressed, exposed, depicted, the visible and the other side. There is a sense of - illusionary reality, thought this might sound contradictory, but contradiction is an inherent character of a photograph or a portrait. It leaves it open to the viewer to interpret it in multiple ways. It is not about the pose, the lighting, the background or many such technical elements but it is the character which makes the reading possible. It is like a text loaded with meaning, it is replete with meaning and meaninglessness. Its open-endedness itself makes it worth a discourse. Its layers need to be viewed rather explored, in order to read it. It is left to the photographer to capture this intangible aspect, thereby erasing the need for a (descriptive) caption. Ellias’s portraits of the famous personalities or the lady seated in the Pushkin Museum, Moscow (which provides a visual frame within a frame), all evidently possess a certain character which is ineffaceable. The figures remain central, not because of what they represent but because of what they are; if the figures are seen in relation to wider social and cultural questions, the images / persons remain equally independent and true to themselves. The portrait photograph is, then, a site of complex series of interactions – aesthetic, cultural, ideological, sociological, and psychological; such that it provides a description of an individual and also the inscription of his / her social identity. As Ellias associates more and more with public spaces, he raises discomforting questions regarding our understanding of - the majority and the minority, the human and the programmed, of power and exploitation, of the humane / logical and the irrational; all which time and again are evaded / dodged by convenience.

The documentary is not about creating an emotionally charged work, which would eventually lead to sympathy pouring. It highlights the political undertones, and points at the urgent need of questioning and understanding the notions of rationality, those of a minority, the subaltern, which invariably draws in their insecurities with which one learns to live. It is about sensitising and understanding the role of - power, strengths and its abuse. The need is to understand the shameful acts born out of mere suspicion and segregations. It wouldn’t be erroneous to say that the highly structured, mundane repetitiveness of life nearly blunts, stales and blinkers ones vision, it ‘automatises’ of our perceptions of and responses to what is seen, sensed, or presented to us in our daily life; be it about individuals, or some events or happenings; such that a slight diversion – an excess or absence of “something”, of the entities having a taken for granted existence, or a look at them from a different lens nearly alters the picture diametrically. It is here that Ellias’s identity of a third person placed within the same world plays an instrumental role. Vrushali Dhage

Reference : |

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|||

|

Picture Courtesy : Rafeeq Ellias

© Text : The Guild. All rights reserved. |

|||||

astic

bodies, to a Kashmiri woman cooking at home; from the two Palestinians

in a tea house to a child being driven back home by his parents from

school, each of them are comfortably nested in their own worlds.

Ellias certainly does not possess an approach of an outsider or a

traveller; rather he senses the need to be a part of the world of

those whom he sees so closely around him; gradually he stages a

comfort zone and nearly shares the same vein.

astic

bodies, to a Kashmiri woman cooking at home; from the two Palestinians

in a tea house to a child being driven back home by his parents from

school, each of them are comfortably nested in their own worlds.

Ellias certainly does not possess an approach of an outsider or a

traveller; rather he senses the need to be a part of the world of

those whom he sees so closely around him; gradually he stages a

comfort zone and nearly shares the same vein. Ellias

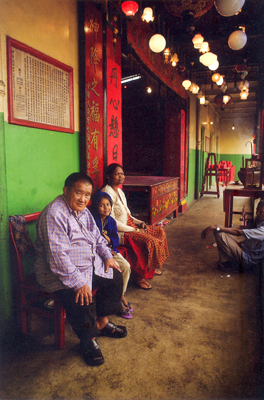

carried his photographic practice ahead with his documentary “The

Legend of Fat Mama”, based on the Indian Chinese community which has

been strongly woven in to the cultural fabric of Kolkata. This

community has long existed – in their own Chinatown; which I would

call a city within a city – sub (set of a) city. Sharing multiple

identities this community is known for their food and celebration.

Like millions of other residents, this community too witnessed the

slow transformation of colonial Calcutta to the post colonial Kolkata.

But they had witnesses something even more, which remains shrouded in

deep recesses of their minds. The Indo-China war of 1962 is one such

milestone, which in the history of our nation needs to be pondered on.

The war proved to be a turning point for the Indian Chinese. The

documentary provides an insight into their lives, as those who were victimised by the terrible cross fire - some who lived and experienced

those days charged with a strong feeling of suspicion and others who

read about it in history books. Some migrated to different countries

while some stayed back to start their living from the scratch,

battling with their insecurities, and, economic and social hurdles. It

is like visualising history as a series of events and discrete images

which speak of the complexities of human experience, disaster and its

after-effects. And yet in the backdrop of the dark happening there are

fond memories too, which act as relieving points.

Ellias

carried his photographic practice ahead with his documentary “The

Legend of Fat Mama”, based on the Indian Chinese community which has

been strongly woven in to the cultural fabric of Kolkata. This

community has long existed – in their own Chinatown; which I would

call a city within a city – sub (set of a) city. Sharing multiple

identities this community is known for their food and celebration.

Like millions of other residents, this community too witnessed the

slow transformation of colonial Calcutta to the post colonial Kolkata.

But they had witnesses something even more, which remains shrouded in

deep recesses of their minds. The Indo-China war of 1962 is one such

milestone, which in the history of our nation needs to be pondered on.

The war proved to be a turning point for the Indian Chinese. The

documentary provides an insight into their lives, as those who were victimised by the terrible cross fire - some who lived and experienced

those days charged with a strong feeling of suspicion and others who

read about it in history books. Some migrated to different countries

while some stayed back to start their living from the scratch,

battling with their insecurities, and, economic and social hurdles. It

is like visualising history as a series of events and discrete images

which speak of the complexities of human experience, disaster and its

after-effects. And yet in the backdrop of the dark happening there are

fond memories too, which act as relieving points.