|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||

|

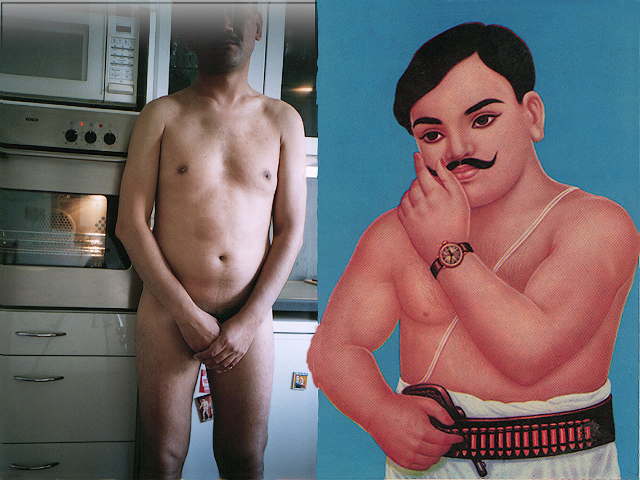

Raju, from the series ‘Mr Malhotra’s Party’, 2007

|

|||||

|

A Subject Revisited

We move around in a world proliferated by the most

rhetorical images that beseech us to feel tempted, look desirable,

aspire, sympathize, feel nostalgic, and what not. It is a world that

is ‘visible’ to us and evidenced by its very representation. To be

witness to an event, and to be seen as being witness to an event, all

constitute the ‘present’. From cameras on cell phones to social

networking websites, we have reached a point where our images

determine our presence and whereabouts in the world. So, what would it

be about the arc of any individual artistic career today that may

interest us, particularly so, in the domain of photography? Moreover,

what role after all does the ‘author’ play any more in this prolific

accumulation of images? Maybe the question might have more pertinence

than mere copyright issues if that artistic career is the

subject, the object, and the narrative of a certain body of

photographic works.

It is not the teleology of Sunil Gupta’s career that moves me as much as how the photographer, his subject-matter (himself many-a-times), and the narrative (i.e. his career) collapse into one and the same entity, the photographs. It is, therefore, not even important whether Sunil Gupta had clicked the photographs himself, or if it is him who has been clicked in them.

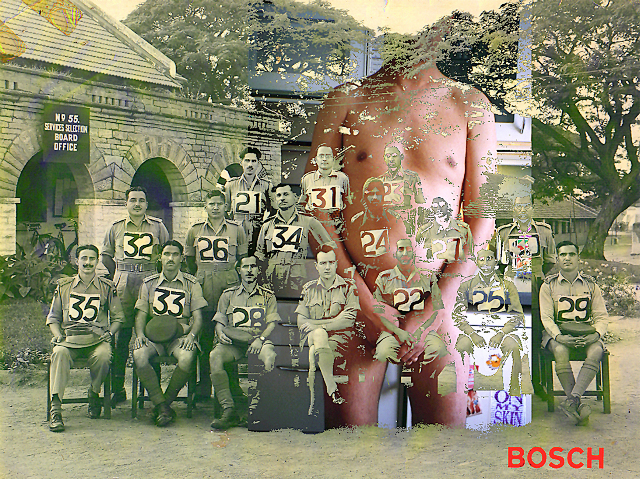

In his earlier series such as Tresspass 2

(1990s), Gupta brought into a single frame, incongruous juxtapositions

of himself on the one hand, and ‘popular’ images or old family

pictures on the

other. He employed the technique of appropriation to

make the use of sources almost immediately accessible and recognizable

in what they don’t show. He had therefore inverted the process of

appropriation, incorporating the unlikely syncopating,

re-contextualizing, and slowing down of discernibility to the point of

estranging notions of the popular. This strategy created space for

thinking about ‘other’ identities through the In Wish You Were Here, however, the series considers the difficulty of documenting knowledge of anyone, and the dependence on the inanimate and mute narratives of pictures (albums, autographs), the tableaux, as well as the anecdotal. But even here, something eludes vision and documentation, and this is not to say that some absence appears in these pictures. Wish you were here is a monographic book of and by Sunil Gupta, that at first glance appears to be just a chronicle of a life lived. Page after page, one finds documented important moments in Gupta’s life, memorable locations, and just about everyone Gupta may have felt a sense of attachment with.

Sunil Gupta’s photographs have rarely amplified the elusiveness of transitory urban life, of cities pulsing with information. On the contrary, he brings to view human networks more complex than the city’s obscured veins of infrastructure, of individual navigating systems within systems. As a narrative, its structure plays with the fragmentary nature of the city, where any corner, any square, any home holds multitudes of stories, looming in an out of view.

Though a Memoir, Sunil’s move casts away the question of veracity in these documentary images, since the document requires its maker to remain outside the document, be it spatially or temporally. Sunil Gupta takes us into a territory we are already very familiar with, i.e., family album photographs, but questions where the maker of any document is situated. The tactic, if we can call it one, is unlike the deliberate and scrupulous manipulation of documents to weave a more complex narrative as in the ‘Re-take of Amrita’ series by Vivan Sundaram. There is also a refrain from citation and irony as in the works by Pushpamala. Though the mode of testimony has burgeoned in a huge way in contemporary Indian art, particularly video art, Gupta initiates a commentary from outside and from within his photographs at the same time, and whether it is his voice of today, or of yesteryears; they become indiscernible. The document, its subject, and its maker are in the same fold. We come across photographs that look similar quite often, but the same can not be said for what this series achieves in unfolding. Mohd. Ahmad Sabih has been involved in doing research and archiving with art-critics, artists and auction houses. His area of interest is in investigating the infrastructure and the institutions of art in the county. [1] Gautam Bhan, Wish You Were Here: Memories of a Gay Life, Sunil Gupta, Yoda Press New Delhi, 2008. |

|||||

|

|

||||

|

Untitled, from the series ‘Tresspass 2’, 1993 |

Kaushiki, from the series ‘Mr Malhotra’s Party’, 2007 |

||||

|

Picture Courtesy : Sunil Gupta

© Text : The Guild. All rights reserved. |

|||||

There

are a range of approaches to the photographs taken as well, mostly

portraits: some are imbued with deep intimacy, some dandy, many that

remind you of family albums, tourist photographs, and still others

taken on the street. None of them, however, compromise on being

stylistically expressive. Yet, there is a haunting nature to this

autobiograph

There

are a range of approaches to the photographs taken as well, mostly

portraits: some are imbued with deep intimacy, some dandy, many that

remind you of family albums, tourist photographs, and still others

taken on the street. None of them, however, compromise on being

stylistically expressive. Yet, there is a haunting nature to this

autobiograph