|

|

|

Sathyanand Mohan

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Afterimages

The three artists who have been

brought together in this section titled Afterimages —

Baiju Parthan, T.V. Santhosh and Shibu Natesan — are all figures

who were instrumental in re-orienting painting away from the

largely narrative focus that it had had until then in India,

towards the question of an ontology of the image itself. They

were among a number of artists in the 1990s who grappled with

the novel representational challenges posed by photography as

well as the electronic and the digital image, in the context of

a life-world increasingly saturated with media images. They

sought to do this by critically addressing the image in its

contexts of circulation and dissemination, and by translating

the processing artifacts of digital transmission and their

idiosyncrasies of resolution and noise into the privileged

medium of painting. Nancy Adajania refers to these aesthetic

concerns collectively as ‘Mediatic Realism’, and situates it in

the historical context of the increasing mediatization of the

life-world in the 1990s, at a time when the global

telecommunications industries established a dominant presence on

the Indian subcontinent for the first time. In Afterimages,

I identify correlations and divergences among the work of these

three artists, and examine their current practice in the light

of this history.

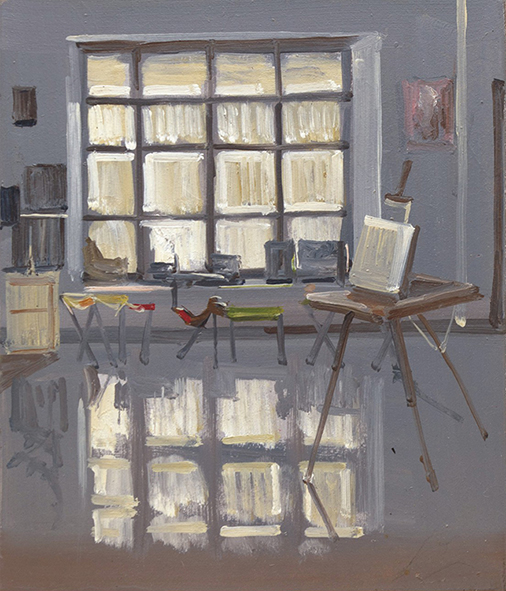

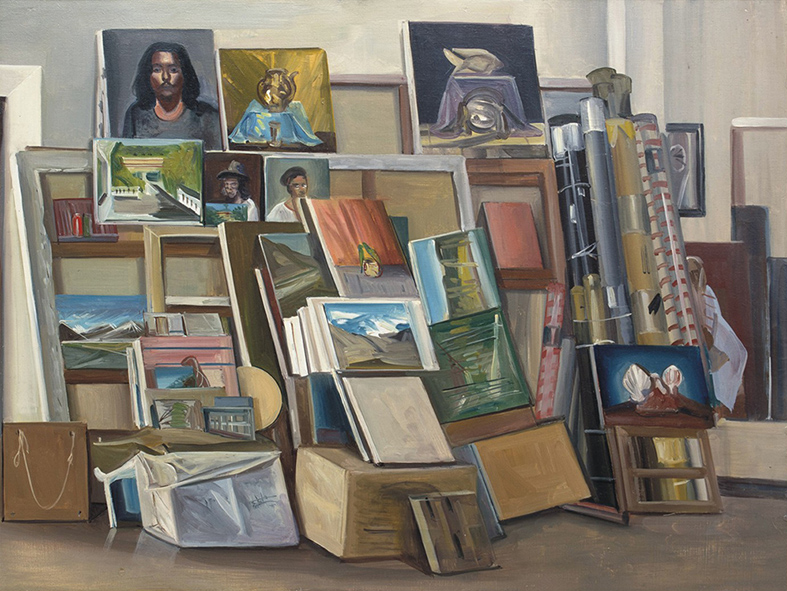

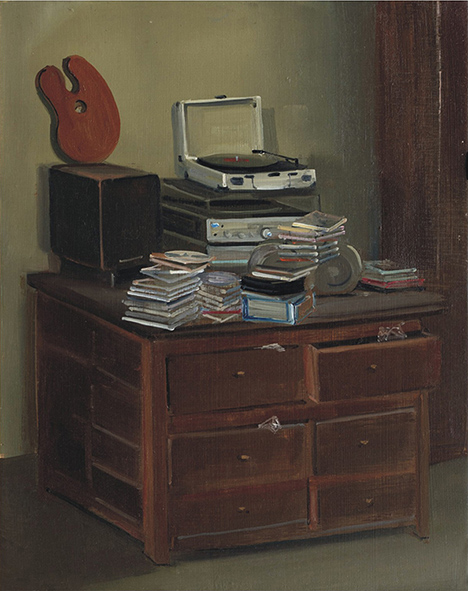

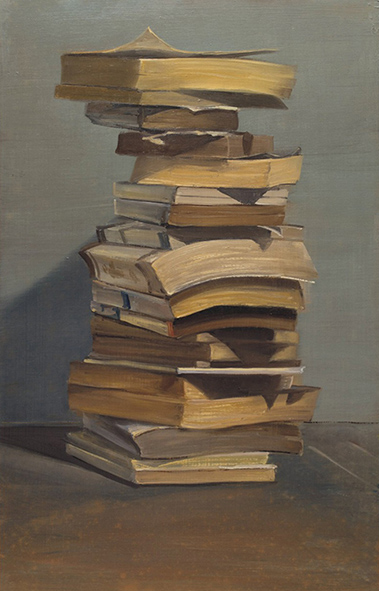

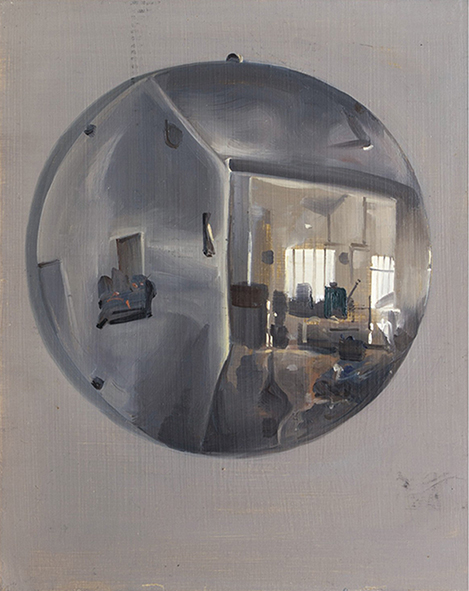

Shibu Natesan’s

work from the 1990s

constitutes one of the earliest attempts in the country to steer

painting towards a consideration of the questions opened up by

the mediated image in the twentieth century, with photography in

particular playing a prominent role in his oeuvre. Natesan’s

practice can be understood in relation to a long history of

painting in the twentieth century which sought to respond to the

ruptures brought about by photography (and later cinema and the

electronic and digital image), and the severing of the mimetic

function that it primarily had until then. However, over the

last decade or so, Natesan’s work has come full circle, and has

gravitated towards a painterly approach where the emphasis is on

a more direct, unmediated relationship to the referent, which he

accomplishes by making the lost art of painting from life (plein

air) a central component of his practice. Coupled with the

alla prima (or wet on wet) technique which

requires that the artist finish the work in a single sitting,

Natesan’s paintings may be understood as a performative staging

of the phenomenological apprehension of what Merleau-Ponty

called the “flesh of the world”, which necessitates this

particular technique and the relatively modest scale of the

work. In the telegraphic economy of the language of painterly

gesture which Natesan employs, he registers this

phenomenological grasping of the fleeting contingency of the

world in its immediacy. At the same time, these works are

already mediated by the history of painting itself, which is

reflexively indicated in them in the attention given to the

space of the studio and the objects in it, which make up an

inventory of the everyday working life of an artist, such as

easels, stretchers, palettes, canvases, books. Natesan’s work

comprises a return to a genre which has had a central (if

largely forgotten) history, and which sought to turn painting

away from the problems of mimesis towards the question of the

embodied apperception of our being in the world.

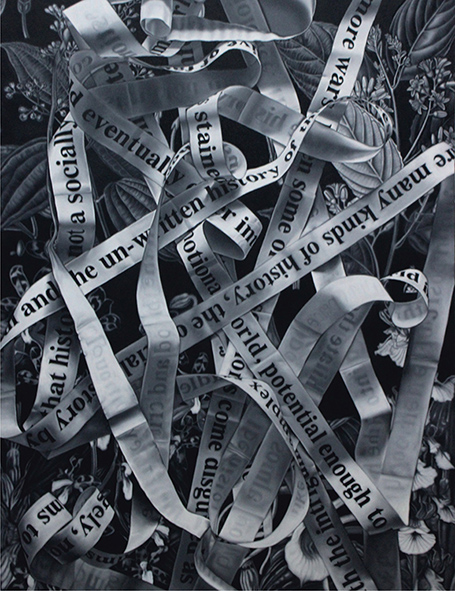

T.V. Santhosh’s

enduring preoccupation

in his work is, as he puts it, the complex riddle that is

History, and our predilection for “so much hatred, chaos and

violence.” Until recently, his paintings were largely defined by

an engagement with the interpellative effects of the electronic

image in everyday life, due to the increasing presence of

televisual media in particular in our lives since the last few

decades. His paintings attempted to critically address the

distance between the reality of endemic social and political

violence and its reification in the circuits of electronic

mediation, through a process in which he literally inverted

image-fragments derived from the technosphere so that its

relationship to the referent was further attenuated. Such

interventions force the viewer to engage in the hermeneutic

labor of deciphering the image, through which a critical

relationship to it is re-established. In more recent work, he

has returned to the allegorical mode that he had explored early

in his career in drawings, watercolors and sculptures. The

paintings exhibited here might be seen as a synthesis of these

two distinct aspects of his practice. While found imagery was

the source of earlier work, in the paintings exhibited here,

Santhosh makes use of staged photographs in order to anchor a

visual idiom that makes extensive use of iconographic symbolism

in the verisimilitude that photography makes possible. The works

expand upon his abiding concern with the spiraling cycles of

violence and war which have marked human history for almost as

long as it has been in existence, and which continues into the

present. In the paintings exhibited here, Santhosh amplifies

these considerations through the use of text printed on scrolls,

which tangle and unfurl against a background of motifs derived

from nature. He thereby situates the interlinked chains of

violence and death which, in his opinion, constitute history —

here allegorically represented through the death rites of a

figure in a gas mask as well as the ticking counter set to its

ominous countdown — against the cyclical processes of decay and

regeneration in the natural world. This ambiguous figuring of

the relationship between History and Nature gives these

paintings their unsettling power.

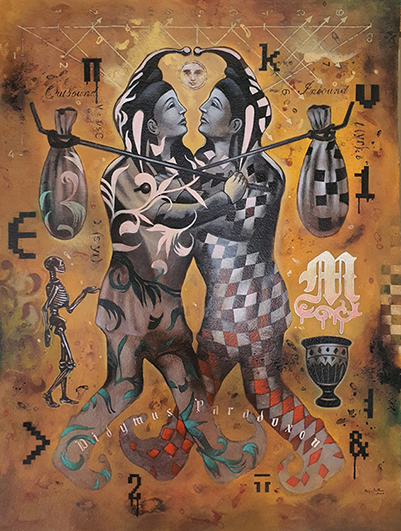

Baiju Parthan’s

work is also

distinguished by a longstanding interest in the creative

possibilities of allegory as an artistic device. Like T.V.

Santhosh and Shibu Natesan, Parthan’s work has been devoted to a

patient excavation of the hyper-mediated landscape that we find

ourselves in today, as well as the ways in which it reframes

normative assumptions about knowledge, experience and

consciousness. An engagement with the many dimensions of the

Virtual — as an aesthetic corollary of digital media, but also

in its philosophical sense, as a metaphysical correlate of the

Real — has long been central to Parthan’s practice. One

direction that this concern takes in his oeuvre, is in terms of

a querying of the invisible architectures which underlie and

shape sense perception and bodily affect, and their interactions

through which the manifest world is experienced and

comprehended. We could say that Parthan conceives of the picture

plane itself as a virtual field, as a space of teeming

potentiality where these occulted forms and their interactions

can be explored or posited in a playful manner. To do this, he

draws upon a wide range of source material — from images and

tropes circulating in the landscape of digital communication and

interaction, to pictorial elements drawn from mathematics, art

history, tarot and semantics. In Twin Paradox for

example, Parthan cites medieval illuminated manuscripts,

alchemical diagrams, as well as the engravings of William Blake

in order to stage an imagined encounter with the technological

singularity, i.e. the moment when artificial intelligence will

gain sentience. The twin paradox is a thought experiment in

special relativity which imagines the interlinked fate of a pair

of twins; the twin that travels to a distant star system upon

returning discovers that the twin who had stayed behind has aged

more. The twins here represent the antinomies within which we

all live today, and represent the confrontation (as well as

symbiotic coexistence) between natural processes on the one

hand, and the iterative algorithmic logics of machine

intelligence, on the other. Parthan’s use of the Fool /

Trickster archetype from the major arcana of the Tarot is used

here to invoke a metaphorical representation of, in his words,

“the approaching singularity where human intelligence will have

to confront its twin, the more than equal Artificial

Intelligence.”

Sathyanand Mohan

Faculty,

Srishti-Manipal Institute of Art, Design and Technology

Bangalore

© Author and The Guild

|

|

|

|

|

Shibu Natesan

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Artist's Studio, Trivandrum, Attingal,

2020, Oil on panel, 12 x 10 inches |

|

Artist's Studio, 2020,

Oil on panel, 7 x 6 inches |

|

Untitled, 2018,

Oil on panel, 14 x 19 inches |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Music System Artist's Home, 2021,

Oil on panel, 11.75 x 9.4 inches |

|

Untitled, 2020,

Oil on panel, 9.4 x 7 inches |

|

Terrace Artist's Home, Attingal Kerala,

2019, Oil on panel, 7 x 9.5 inches |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Artist's Studio, Attingal, 2020,

Oil on panel, 7 x 5 inches |

|

Untitled, 22/07/2021,

Oil on panel, 22 x 13 inches |

|

Gate - 8 Artist's Home, 2018,

Oil on panel, 14 x 19 inches |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Untitled, 2022,

Oil on panel, 12 x 9.6 inches |

|

Paint Tins, 2021,

Oil on panel, 12 x 10 inches |

|

Untitled, 2022,

Oil on panel, 11.8 x 9.5 inches |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

T. V. Santhosh |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Protagonist and his Empty Rat Trap - II,

2022, oil on canvas, 72 x 96 inches (diptych) |

|

Jumbled Monologue - II,

2022, oil on canvas, 48 x 36 inches |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Baiju Parthan |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mystery and Knowledge,

(Mysterium Et Scientia), 2022

Acrylic on Canson paper,

40 x 30 inches |

|

Twin Paradox,

(Didymus Paradoxon), 2022

Acrylic on Canson paper,

40 x 30 inches |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

![]()