|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

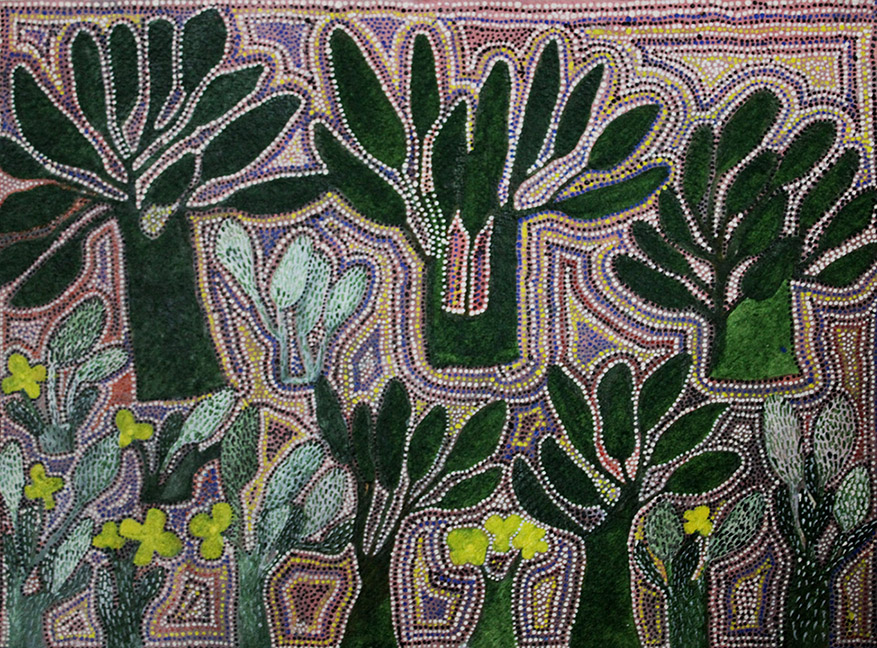

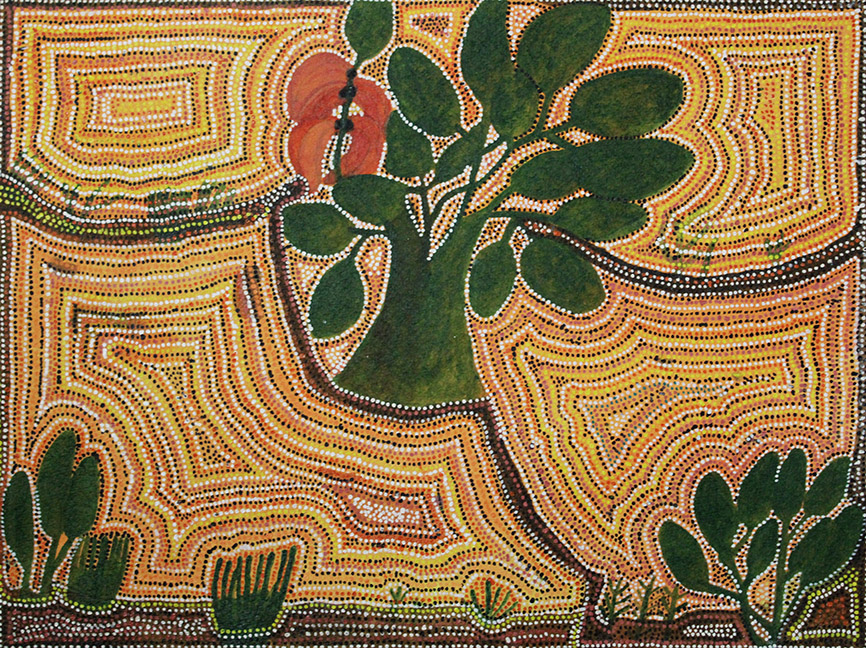

Untitled 1, 2020, watercolour on paper,

11 x 15 inches. |

|

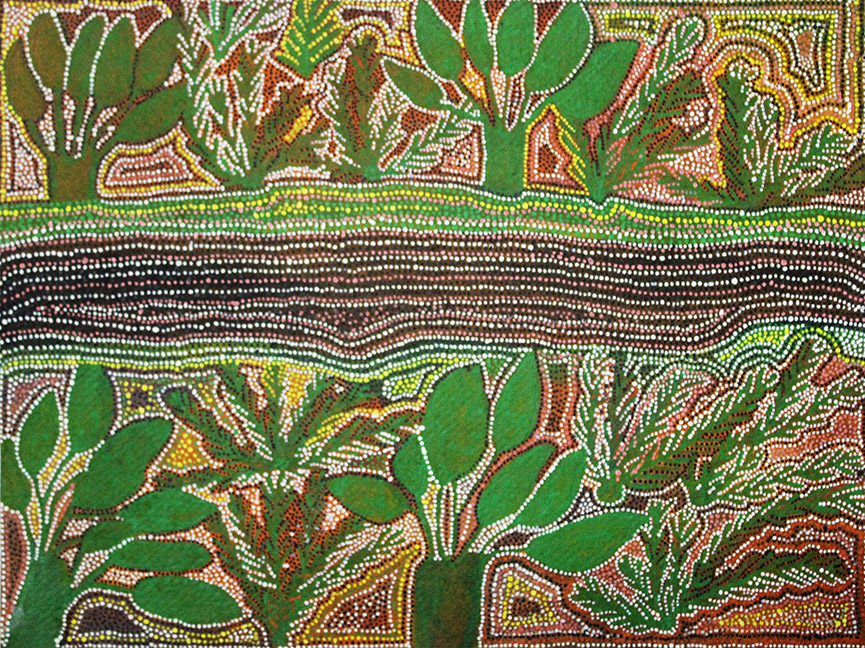

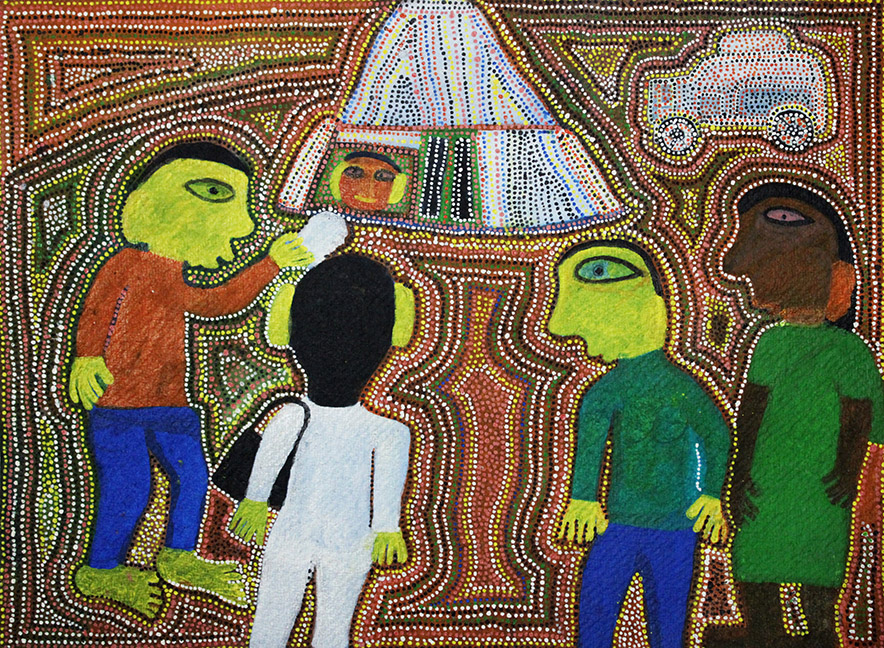

Untitled 2, 2020, watercolour on paper,

11 x 15 inches. |

|

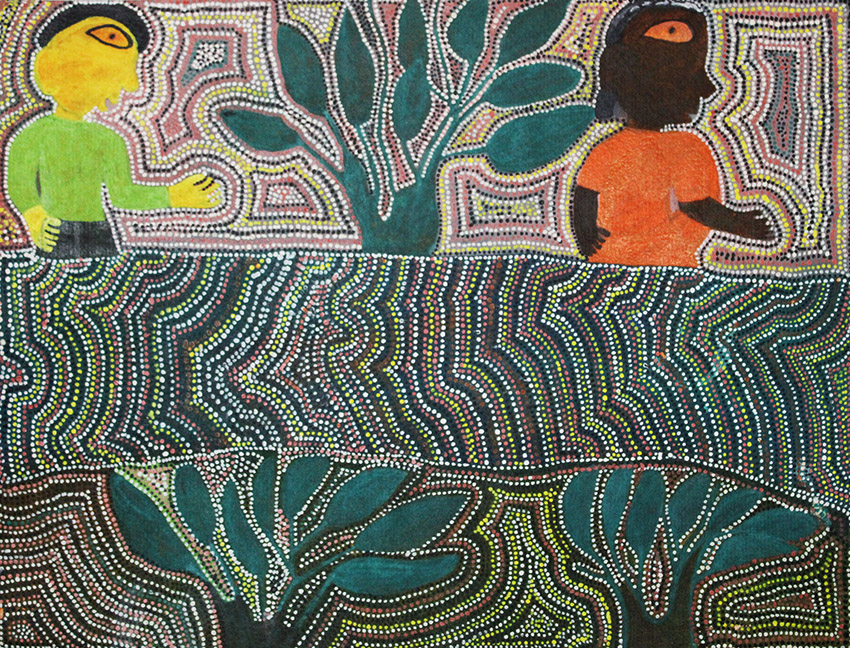

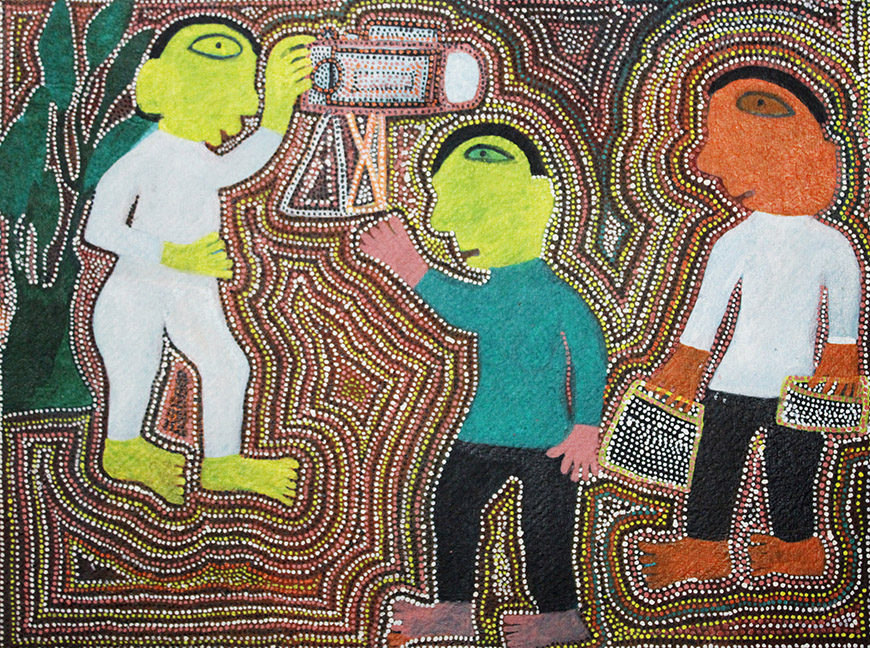

Untitled 3,

2020, watercolour on paper,

11 x 15 inches. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

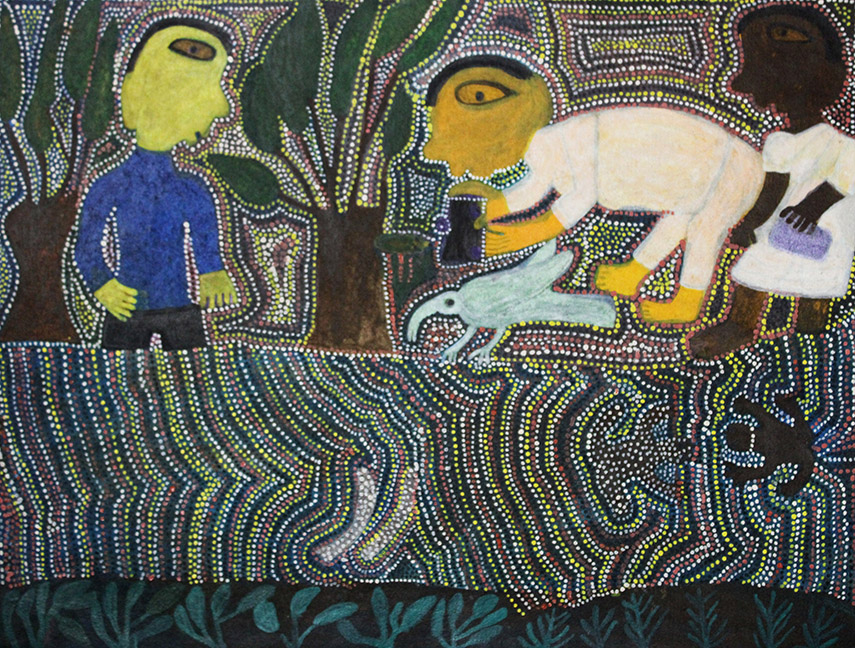

Untitled 4, 2020, watercolour on paper,

11 x 15 inches. |

|

Untitled 5,

2020, watercolour on paper,

11 x 15 inches. |

|

Untitled 6, 2020, watercolour on paper,

11 x 15 inches. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Untitled 7, 2020, watercolour on paper,

11 x 15 inches. |

|

Untitled 8, 2020, watercolour on paper,

11 x 15 inches. |

|

Untitled 9, 2020, watercolour on paper,

11 x 15 inches. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Untitled 10, 2020, watercolour on paper,

11 x 15 inches. |

|

Untitled 11, 2020, watercolour on paper,

11 x 15 inches. |

|

Untitled 12, 2020, watercolour on paper,

11 x 15 inches. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Untitled 13, 2020, watercolour on paper,

11 x 15 inches. |

|

Untitled 14, 2020, watercolour on paper,

11 x 15 inches. |

|

Untitled 15, 2020, watercolour on paper,

11 x 15 inches. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Untitled 16, 2020, watercolour on paper,

11 x 15 inches. |

|

Untitled 17, 2020, watercolour on paper,

11 x 15 inches. |

|

Untitled 18, 2020, watercolour on paper,

11 x 15 inches. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Untitled 19, 2020, watercolour on paper,

11 x 15 inches. |

|

Untitled 20, 2020, watercolour on paper,

11 x 15 inches. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Shantibai: An Expedition to Bailadila

Mines

The set of twenty watercolour

paintings by Shantibai take us on a journey through the Bailadila

Range in South Chhattisgarh to the iron ore mines. One of their

regular expeditions to these sites with her artist colleague Navjot

Altaf and friend Ravirendra

before the pandemic took over. The

paintings record the scenes encountered during her journey – trees,

plants and flowers, river and water creatures, shrine, and people,

ending with a detailed depiction of the mining activities and

snippets of their time spent at the site. In a nutshell, these

folios form a visual diary recording memorable moments of the

journey. Such portrayal of surroundings, daily life and experiences

are integral to the indigenous art forms, in this case, the Gondi

visual repertoire, which Shantibai has strong connections with.

Shantibai chooses to portray

selective elements in each of these paintings. The sculpturesque

trees and shrubs bearing fruits and flowers predominantly emerge

against the dotted backdrop. In this pictorial game, dots traverse

the length and breadth of the surface of the painting creating fluid

forms. There are zones that get demarcated by these running dots

that turn into fields, roads, swirls of the river, excavated fields,

or heaps of ore. Every surface stands out as a part of a picture

puzzle that can be removed and put back again. The human figures

Shantibai brings into these paintings bear significant reference to

the figures in her sculptures. Here too, they are marked with

well-defined wide eyes that stand as witnesses to the narratives of

the paintings.

The time of the creation of these paintings becomes

extremely important. Made during the pandemic times, and in the

period of lockdown and the aftermath, these paintings are inevitably

coloured with the crisis of our current times: the conflict between

humans and nature that the invisible virus has brought forth for

reflections. Shantibai features the land, water and forests as sites

for deliberations. Her own voice is quiet and almost invisible. From

a surface level, the paintings depict her journey to Bailadila

through various scenes she encounters. These are accompanied by the

utmost simple notes. For instance:

“ये

जंगल के बीच में रोड हैं, हम बैलाडिला जा रहें है। और उधर से ट्रैक्टर

आ रहा था।”

(We are on our way

to Bailadila mines through the road within the forest. A tractor is

coming from the other side).

Yet, the idea of the road through the forest, land mines located in

the middle and the truck unsettle our thoughts. Through these

illustrious paintings, we are introduced to the flora and fauna,

learn about the uses of plants, see people’s lives around the river,

spot the spaces of worship, and experience the joy of the author in

her watching the riverside. And then, we enter another terrain. Here

the flourishing land is being dug up, crushed, melted and

transported away. In other words, the land is being invaded. But

Shantibai does not intend to contrast the two worlds. Rather, she

renders the mining activities with the same observance in which she

shows women plucking leaves on the riverside. The Palash tree

and the giant mining machine are represented with the same gaze and

intensity. Thus she leaves it to the viewer to construct meanings.

The images of Shantibai cities hit back at us hard and challenge our

conscience. Can we see the forest and river without thinking of the

State and its developmental policies? Can we think of inhabitants of

this land without thinking of their displacement? Can we look at the

image of the idol of Mata ignoring the way the indigenous

religious spaces and practices are invaded? Can we be mesmerized by

the mining site forgetting the forest covers the region has lost?

ये घना जंगल है, ये दो कास वहीं का है…

(Ye

Ghana Jungle hai, ye do Kaas vanhi ka hai...)

Notes by Shantibai

Back to the exhibition |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

![]()